Learning Japanese with Just One Character

Did you know that in Japanese, just one single character—both in writing and pronunciation—can carry a full and clear meaning?

Unlike English, where even simple words like “eye” or “sun” require three letters, Japanese often uses just one kanji and one sound (like “目” read as me) to express the same idea.

Even better? Many of these one-character words are used in everyday conversation.

In this post, we’ll explore some of these ultra-minimal yet powerful words, complete with emojis and example vocabulary!

🩸 血(ち / chi) – blood

The kanji 血 means blood, and it’s used in contexts related to the body, health, family lineage, and even strong emotions or violence in literature and culture.

Reading:

- ち (chi) – kun’yomi (native Japanese reading), used in daily expressions

- けつ (ketsu) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading), used in compound words like 出血 or 献血

Kanji Origin:

血(Chi / ketsu) is a pictograph(象形文字) that originally represented a container with blood inside.

In ancient scripts, it showed a bowl or vessel holding liquid, symbolizing blood as a life-giving or vital substance.

While the dot-like mark (丶) may resemble a droplet, it is not a separate radical. The character as a whole originated as a pictograph of a vessel containing blood, symbolizing the concept of blood as a vital substance.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 血液(けつえき / ketsueki)=blood (formal term)

- 出血(しゅっけつ / shukketsu)=bleeding

- 献血(けんけつ / kenketsu)=blood donation

- 血圧(けつあつ / ketsuatsu)=blood pressure

Common Collocations:

✅ 血が出る (Chi ga deru) – to bleed

転んでひざから血が出ました。

EN: I fell and my knee started bleeding.

✅ 血を流す(Chi wo nagasu) – to shed blood

戦争では多くの人が血を流しました。

EN: Many people shed blood in the war.

✅ 血が止まらない (Chi ga tomaranai) – the bleeding won’t stop

血が止まらないときは病院に行ってください。

EN: If the bleeding doesn’t stop, go to the hospital.

✅ 血液型 (Ketsuekigata) – blood type

あなたの血液型は何ですか?

EN: What’s your blood type?

✍️ Notes:

- ち is used in native expressions and casual conversation.

- けつ appears in compound medical or technical words.

- Blood-related terms are often important in Japanese culture—for example, blood type is sometimes linked to personality in popular media.

✋ 手(て / te) – hand

The kanji 手 means hand, and it is one of the most essential kanji in Japanese. It symbolizes physical action, skill, help, and even communication.

Reading:

- て (te) – kun’yomi (native Japanese reading), common in everyday use

- しゅ (shu) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading), used in compound words like 選手 or 手術

Kanji Origin:

手(te / shu) is a pictograph(象形文字) that originally depicted an open hand with fingers extended. In ancient scripts such as oracle bone inscriptions, it resembled a palm with spread fingers, clearly illustrating the concept of a hand.

The modern form is simplified but still retains the basic outline of a hand, including fingers and wrist. Because the hand plays a central role in most physical and social activities, this kanji appears in many words related to action, assistance, skill, and interaction.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 手紙(てがみ / tegami)=letter (literally “hand + paper”) ←The “ga” sound comes from rendaku(連濁).

- 手伝う(てつだう / tetsudau)=to help

- 選手(せんしゅ / senshu)=athlete, player

- 手術(しゅじゅつ / shujutsu)=surgery

Common Collocations:

✅ 手を洗う (te wo arau) – to wash hands

ごはんの前に手を洗いましょう。

EN: Let’s wash our hands before eating.

✅ 手をつなぐ (te wo tsunagu) – to hold hands

子どもと手をつないで歩きます。

EN: I walk holding hands with my child.

✅ 手がかかる (te ga kakaru) – to require a lot of care or effort

この仕事は手がかかります。

EN: This job takes a lot of effort.

✅ 手を貸す (te wo kasu) – to lend a hand, help out

ちょっと手を貸してくれませんか?

EN: Could you give me a hand?

✍️ Notes:

- て is used in daily conversation and native expressions.

- しゅ appears in compound words, especially in formal or professional terms.

- 手 also plays an important role in idiomatic expressions and grammar, often expressing ability, effort, or involvement.

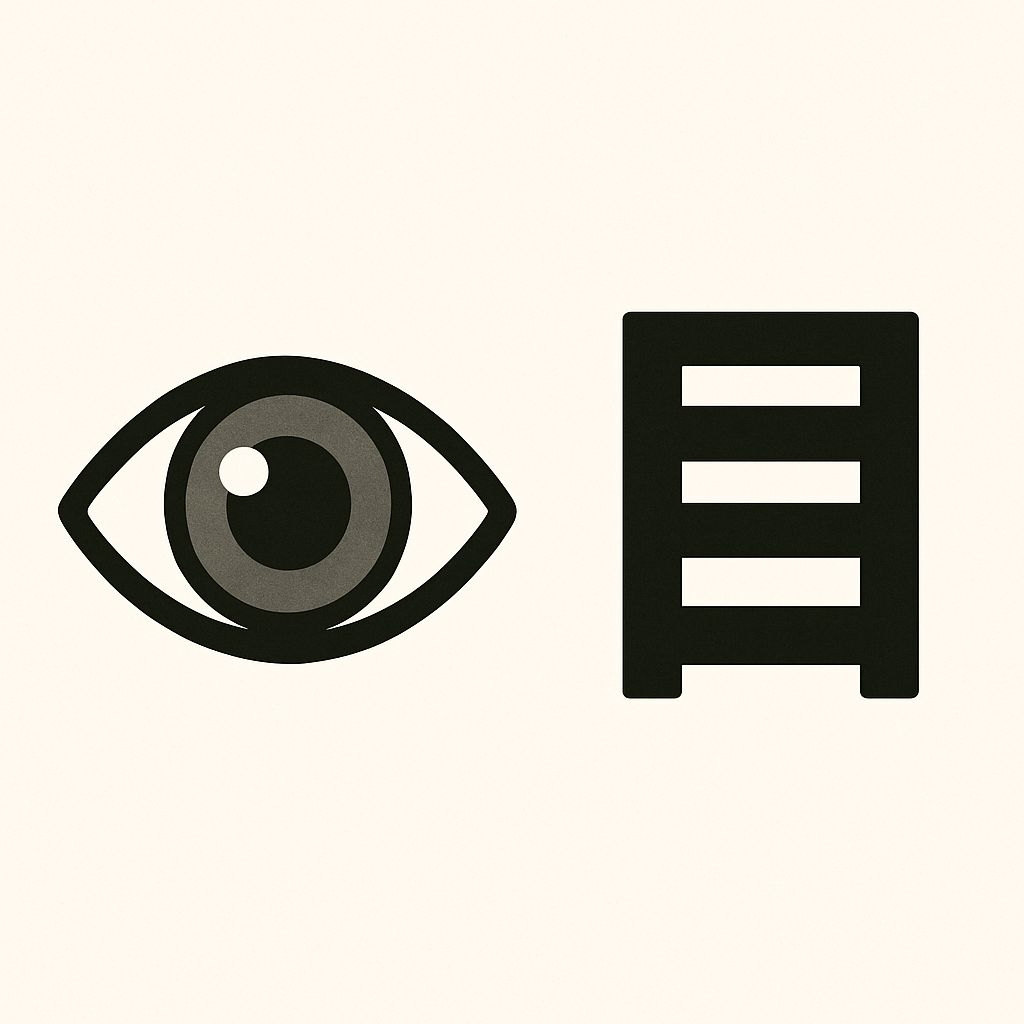

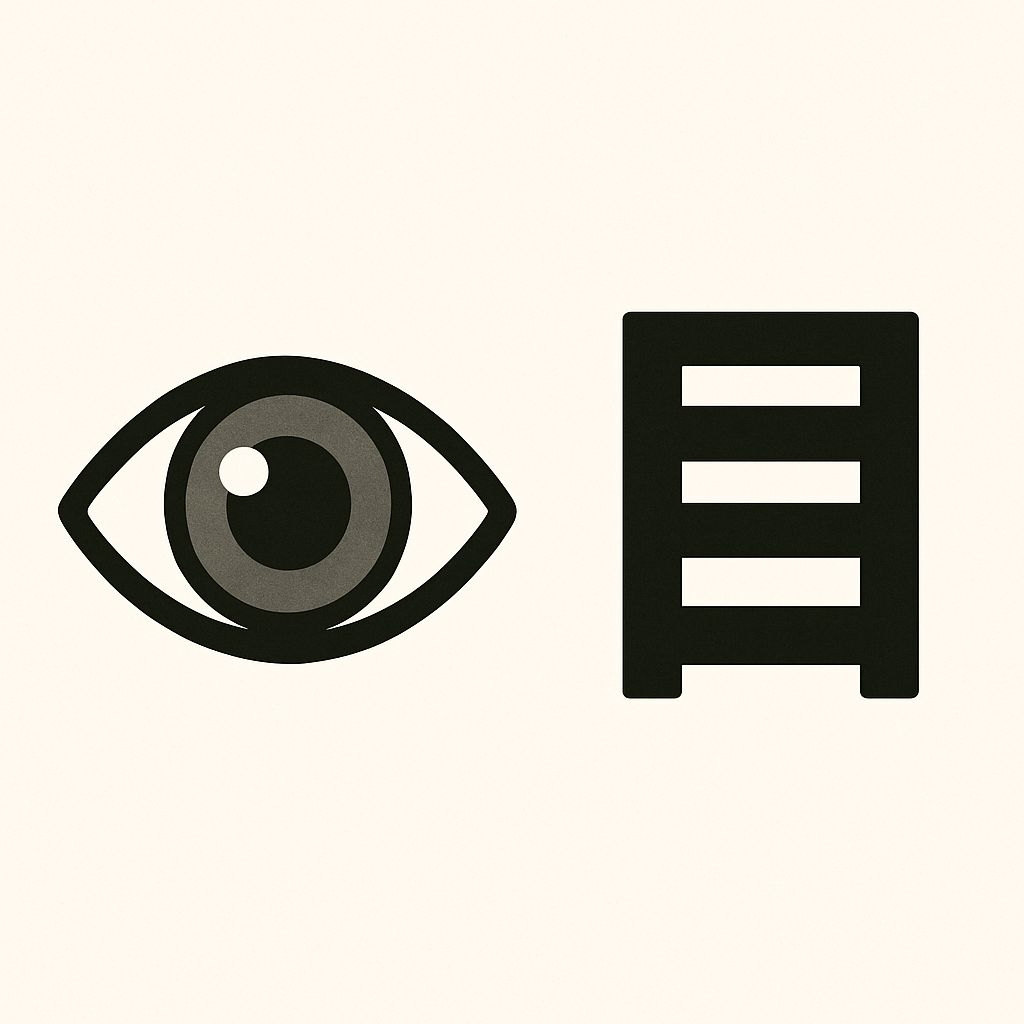

👁️ 目(め / me) – eye

The kanji 目 means eye and is one of the most basic and commonly used kanji in Japanese. It refers not only to the physical eye but also to perception, viewpoint, and order.

Reading:

- め (me) – kun’yomi (native Japanese reading), used in conversation and basic words

- もく / ぼく (moku / boku) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading), used in compound words like 目的 or 注目

Kanji Origin:

目 (me / moku) is a pictograph(象形文字). In ancient scripts, it was drawn as a simple yet recognizable image of an eye, often with a central line or dot to suggest the pupil.

The modern form still resembles a vertical eye shape, making it one of the easiest kanji to recognize and remember.Since the eye is associated with seeing, observing, and evaluating, 目 is also used in words related to rank, order, attention, and perspective.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 目標(もくひょう / mokuhyō)=goal, target

- 注目(ちゅうもく / chūmoku)=attention

- 目的(もくてき / mokuteki)=purpose

- 一日目(いちにちめ / ichinichime)=first day

Common Collocations:

✅ 目が痛い (me ga itai) – eyes hurt

パソコンを使いすぎて目が痛いです。

EN: My eyes hurt from using the computer too much.

✅ 目が悪い (me ga warui) – to have bad eyesight

私は目が悪いので、メガネをかけています。

EN: I have poor eyesight, so I wear glasses.

✅ 目を閉じる (me wo tojiru) – to close one’s eyes

リラックスするために目を閉じました。

EN: I closed my eyes to relax.

✅ 目を引く (me wo hiku) – to attract attention

そのドレスはとても目を引きます。

EN: That dress really catches the eye.

✍️ Notes:

- 目 is one of the earliest kanji taught to learners, often appearing in simple children’s books.

- Its metaphorical use is very common: “keeping an eye on something,” “catching someone’s eye,” etc.

- In grammar, 〜目(〜め) is also used to indicate order or position, like 「一つ目」(the first one) or 「三日目」(the third day).

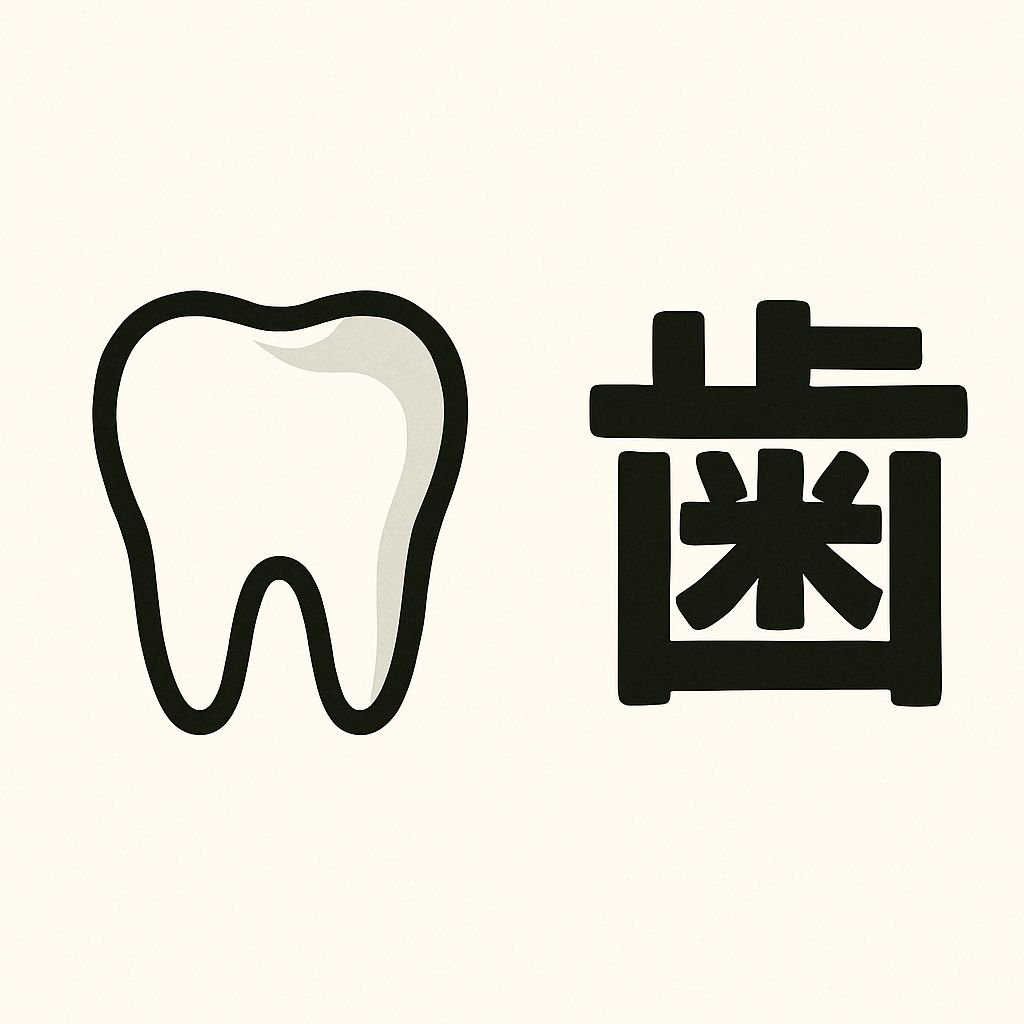

🦷 歯(は / ha) – tooth

The kanji 歯 means tooth and is used in both literal and metaphorical expressions related to teeth, chewing, speaking, and even determination.

Reading:

- は (ha) – kun’yomi (native Japanese reading), common in daily conversation

- し (shi) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading), used in compound words (e.g., 歯科)

Kanji Origin:

歯 (ha / shi) is a compound ideograph(会意文字) that originally represented the idea of chewing or grinding with teeth. The upper component is thought to depict teeth arranged in a row, while the lower part includes 米 (rice), symbolizing food, and 止 (stop), which may have been added for structural or phonetic reasons rather than meaning.Although visually complex, the character reflects the essential function of teeth in breaking down food.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 歯医者(はいしゃ / haisha)=dentist

- 歯磨き(はみがき / hamigaki)=tooth brushing

- 歯科(しか / shika)=dentistry

- 虫歯(むしば / mushiba)=cavity, bad tooth ←The “ba” sound comes from rendaku(連濁).

Common Collocations:

✅ 歯が痛い (ha ga itai) – to have a toothache

甘いものを食べたら歯が痛くなりました。

EN: My tooth started hurting after eating sweets.

✅ 歯を磨く (ha wo migaku) – to brush one’s teeth

毎晩、歯を磨きます。

EN: I brush my teeth every night.

✅ 歯が抜ける (ha ga nukeru) – a tooth falls out

子どもの歯が抜けました。

EN: My child lost a tooth.

✅ 歯を大切にする (ha wo taisetsu ni suru) – to take care of one’s teeth

歯を大切にしましょう。

EN: Let’s take good care of our teeth.

✍️ Notes:

- は is used in conversation and native phrases (e.g., 歯が痛い).

- し is used in compound words, especially medical terms (e.g., 歯科医=dentist).

- In Japanese culture, dental care is highly emphasized, and words with 歯 appear in daily routines, health education, and products.

🫁 胃(い / i) – stomach

The kanji 胃 means stomach, and it’s commonly used in medical, health, and daily situations in Japanese.

Reading:

- い (i) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading)

※ No commonly used kun’yomi (native Japanese reading)

Kanji Origin:

胃 (i) is a compound ideograph(会意文字)formed from two parts:

⺼ (nikuzuki), the “meat” or “flesh” radical, indicates a part of the body;

田 (ta), usually meaning “rice field,” is used symbolically to represent a compartment or structured space — likely referring to an internal organ.

Together, they express the idea of an internal body organ — the stomach, where food is stored and digested.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 胃痛(いつう / itsū)=stomachache

- 胃薬(いぐすり / igusuri)=stomach medicine ←The “gu” sound comes from rendaku(連濁).

- 胃腸(いちょう / ichō)=stomach and intestines

Common Collocations:

✅ 胃が痛い (i ga itai) – to have a stomachache

ストレスで胃が痛いです。

EN: My stomach hurts from stress.

✅ 胃が強い (i ga tsuyoi) – to have a strong stomach

彼は胃が強いから、辛いものも平気です。

EN: He has a strong stomach, so spicy food doesn’t bother him.

✅ 胃が弱い (i ga yowai) – to have a weak stomach

私は胃が弱いので、油っこい食べ物は苦手です。

EN: I have a weak stomach, so oily food doesn’t agree with me.

✅ 胃薬を飲む(igusuri wo nomu) – to take stomach medicine

食べすぎたので、胃薬を飲みました。

EN: I ate too much, so I took some stomach medicine.

✍️ Notes:

- In Japanese, the stomach is often expressed as the subject of the sentence (“胃が~”) when describing physical states.

- 胃 is also widely used in medical vocabulary — learning this one character helps unlock many health-related terms!

🐶 毛(け / ke) – hair, fur

The kanji 毛 means hair, fur, or bristles. It refers to the fine strands that grow on the body, especially animal fur, body hair, and texture in general.

Reading:

- け (ke) – kun’yomi (native Japanese reading), used in basic, everyday expressions

- もう (mō) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading), used in compound words like 毛布 or 体毛

Kanji Origin:

毛 (ke / mō) is a pictograph(象形文字). In ancient scripts, it was drawn as lines extending upward from a base, representing strands of hair or fur growing from the skin.

The modern form is simplified but still resembles a tuft or single hair, making the meaning easy to remember thanks to its visual resemblance.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 体毛(たいもう / taimō)=body hair

- 毛布(もうふ / mōfu)=blanket (literally: “hair + cloth”)

- 毛糸(けいと / keito)=wool yarn

Common Collocations:

✅ 毛が抜ける (ke ga nukeru) – hair/fur falls out

春になると犬の毛がたくさん抜けます。

EN: In spring, my dog sheds a lot of fur.

✅ 毛が生える (ke ga haeru) – hair grows

赤ちゃんの頭に毛が生えてきました。

EN: Hair has started to grow on the baby’s head.

✅ 毛を剃る (ke wo soru) – to shave hair

足の毛を剃りました。

EN: I shaved the hair on my legs.

✍️ Notes:

- け is used for general body or animal hair, and is very common in daily speech.

- もう is used in more technical or compound vocabulary (especially in formal or product-related terms).

- In Japanese, hair is often classified: 髪(かみ)=head hair, 毛=body/fur/bristle, which can be confusing at first!

🔥 火(ひ / hi)– fire

The kanji 火 means fire and is used in a wide range of contexts—from literal flames to symbolic meanings like passion, danger, or heat.

Reading:

- ひ (hi) – kun’yomi (native Japanese reading), commonly used in daily expressions

- か (ka) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading), used in compound words like 火山(かざん)=volcano

Kanji Origin:

火 (hi / ka) is a pictograph(象形文字). In ancient scripts, it was drawn as a blazing flame, with upward lines representing rising fire.

The modern character retains this visual structure, showing stylized flames and a central stroke suggesting the fire’s core.

This powerful and dynamic kanji symbolizes not only heat, light, and energy, but also the potential for destruction — making it a symbol deeply connected to both nature and human life.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 火事(かじ / kaji)=fire (accidental or destructive fire)

- 火山(かざん / kazan)=volcano ←The “za” sound comes from rendaku(連濁).

- 花火(はなび / hanabi)=fireworks ←The “bi” sound comes from rendaku(連濁).

- 火曜日(かようび / kayōbi)=Tuesday (“fire day” in Japanese calendar naming)

Common Collocations:

✅ 火をつける (hi wo tsukeru) – to set fire / to ignite

キャンプで火をつけました。

EN: I lit a fire at the campsite.

✅ 火が出る (hi ga deru) – a fire breaks out

台所から火が出ました。

EN: A fire broke out in the kitchen.

✅ 火を消す (hi wo kesu) – to put out a fire

火を消してください。

EN: Please put out the fire.

✅ 火に強い (hi ni tsuyoi) – fire-resistant

この素材は火に強いです。

EN: This material is fire-resistant.

✍️ Notes:

- In compound words, the on’yomi か is most commonly used (e.g., 火山, 火災).

- In conversation, the kun’yomi ひ is more common, especially in physical descriptions or instructions.

🌳 木(き / ki)– tree, wood

The kanji 木 means tree or wood, and it’s one of the most basic and visually intuitive kanji in Japanese. It’s used in words related to nature, materials, and even time (like weekdays).

Reading:

- き (ki) – kun’yomi (native Japanese reading), used in simple, everyday words

- もく / ぼく (moku / boku) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading), used in compound words (e.g., 木曜日)

Kanji Origin:

木 (ki/moku/ko) is a classic pictograph(象形文字) that originally depicted a tree, showing a trunk and branches.

The modern form preserves this image: the vertical stroke represents the trunk, and the diagonal strokes represent the branches. While some interpretations describe the bottom horizontal stroke as roots, this is more symbolic than historically confirmed.

Because of its simple, recognizable form and clear meaning, 木 is one of the easiest kanji for beginners to learn — and a great introduction to kanji related to nature and the environment.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 木曜日(もくようび / mokuyōbi)=Thursday (“wood day” in the Japanese calendar)

- 木材(もくざい / mokuzai)=lumber, timber

- 木陰(こかげ / kokage)=shade of a tree

- 木の葉(このは / konoha)=tree leaves

Common Collocations:

✅ 木を植える (ki wo ueru) – to plant a tree

庭に木を植えました。

EN: I planted a tree in the yard.

✅ 木が倒れる (ki ga taoreru) – a tree falls

台風で木が倒れました。

EN: A tree fell due to the typhoon.

✅ 木のにおい (ki no nioi) – the smell of wood

私は木のにおいが好きです。

EN: I like the smell of wood.

✅ 木の下 (ki no ↓) – under a tree

木の下でお弁当を食べました。

EN: I ate lunch under the tree.

✍️ Notes:

- 木 is one of the five elements (五行 / ごぎょう) in traditional East Asian thought: 木・火・土・金・水 (wood, fire, earth, metal, water).

- In modern Japanese, it appears in weekday names and natural or material-related compounds.

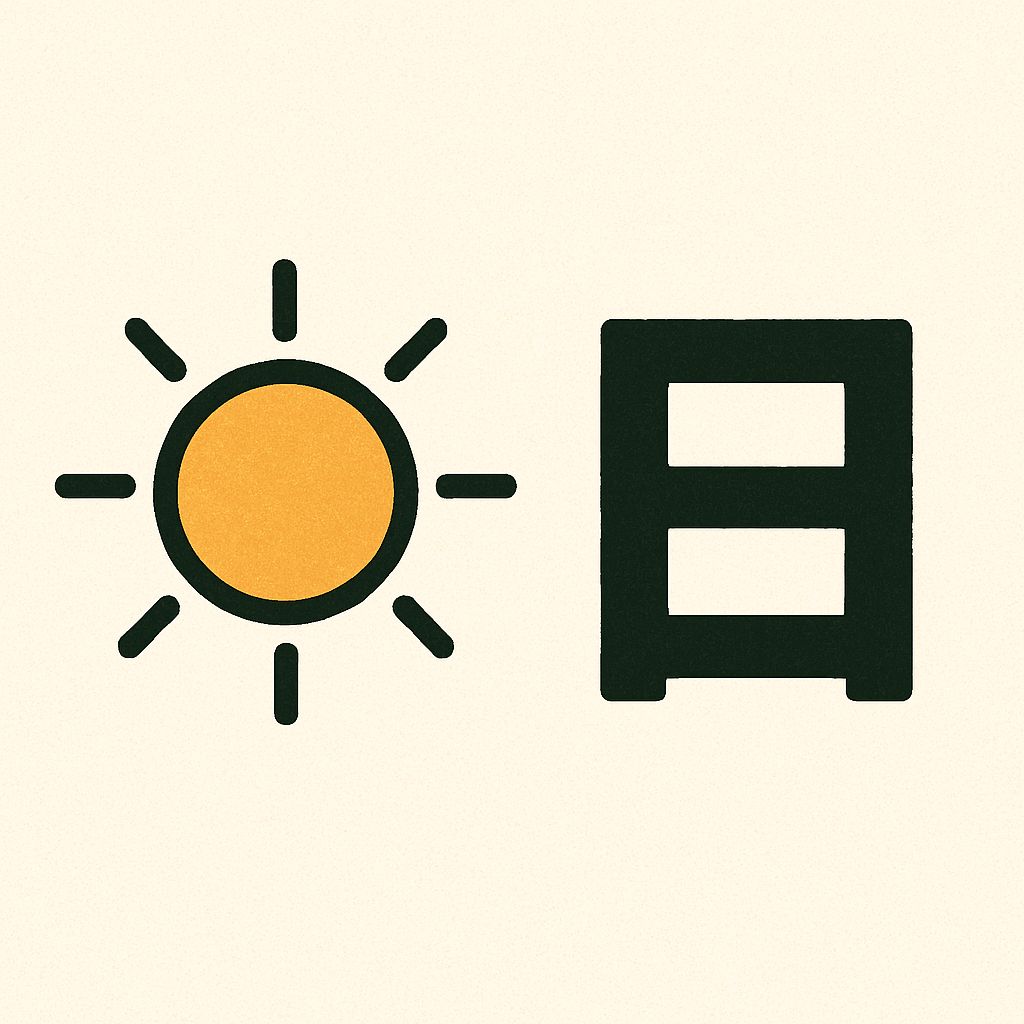

☀️ 日(ひ / hi)– sun, day

The kanji 日 means both sun and day, and it’s one of the most frequently used characters in Japanese. It appears in dates, days of the week, times of day, holidays, and more.

Reading:

- ひ (hi) – kun’yomi (native Japanese reading), used for sun and day in natural expressions

- にち / じつ (nichi / jitsu) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading), used in compound words like 日曜日 or 休日

Kanji Origin:

日 (hi / nichi) is a pictograph(象形文字) representing the sun. In early scripts such as oracle bone inscriptions, it appeared as a circle with a central dot or short line, symbolizing the sun and its radiance.

As writing evolved, this circular form was stylized into a square with a horizontal stroke, becoming the modern shape. Because the sun was central to measuring time in ancient cultures, this kanji came to represent both sunlight and the passage of time — particularly a single day.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 今日(きょう / kyō)=today

- 日曜日(にちようび / nichiyōbi)=Sunday

- 日光(にっこう / nikkō)=sunlight

- 休日(きゅうじつ / kyūjitsu)=holiday

Common Collocations:

✅ 日がのぼる (hi ga noboru) – the sun rises

朝6時に日がのぼります。

EN: The sun rises at 6 a.m.

✅ 日が沈む (hi ga shizumu) – the sun sets

海に日が沈んでいきます。

EN: The sun is setting into the sea.

✅ 日が長い / 短い (hi ga nagai / mijikai) – the day is long / short

夏は日が長いです。

EN: The days are long in summer.

✅ いい日 (Ī hi)– a good day

今日はいい日ですね。

EN: It’s a nice day today.

✍️ Notes:

- When referring to the sun, the reading is usually ひ (hi).

- When used in compound words or dates, the reading is often にち or じつ.

(e.g., 誕生日 = birthday, 国民の休日 = national holiday) - 日 is part of the calendar system in Japan, including days of the week and official holidays.

⏳ 間(ま / ma)– space, interval, timing

The kanji 間 expresses the idea of space, time, or a gap between things. It can refer to physical distance, time intervals, or even timing in conversation and social situations.

Reading:

- ま (ma) – kun’yomi (native Japanese reading), often used in daily phrases

- かん (kan) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading), common in compound words like 時間 or 瞬間

Kanji Origin:

間 (ma / aida) is a compound ideograph(会意文字) composed of 門 (gate) and 日 (sun). In early scripts, it depicted the sun seen through the opening of a gate, visually expressing the concept of a space or interval.

This character carries rich metaphorical meaning and is used in a wide range of contexts — including time (duration, moment), space (gap, room), relationships (distance or connection), and even timing or chance (as in good or bad fortune).

Vocabulary Examples:

- 時間(じかん / jikan)=time

- 間隔(かんかく / kankaku)=interval, spacing

- 瞬間(しゅんかん / shunkan)=moment, instant

- 人間(にんげん / ningen)=human being (literally: “between people”)

Common Collocations:

✅ 間が悪い (ma ga warui) – to have bad timing / to feel awkward

Used when something happens at the wrong moment or creates an uncomfortable situation.

彼氏と喧嘩しているときに、間が悪く友人に会ってしまった。

EN: I happened to run into a friend while I was fighting with my boyfriend—it was really awkward.

✅ 間がいい (ma ga Ī) – to have good timing / to arrive at just the right moment

ちょうどご飯ができたところ。間がいいね!

EN: Dinner’s ready—you have perfect timing!

✅ 間に合う (ma ni au) – to make it in time

電車に間に合いました。

EN: I made it to the train on time.

✅ 間を取る (aida wo toru) – to find a compromise / balance

二人の意見の間を取って決めましょう。

EN: Let’s find a middle ground between the two opinions.

Notes:

- ま focuses on timing, pauses, atmosphere, and is often used in native expressions.

- かん appears in more formal or compound terms relating to time and intervals.

- The expression 間が悪い doesn’t mean “bad space” literally—it means the atmosphere or timing feels off, often socially or emotionally.

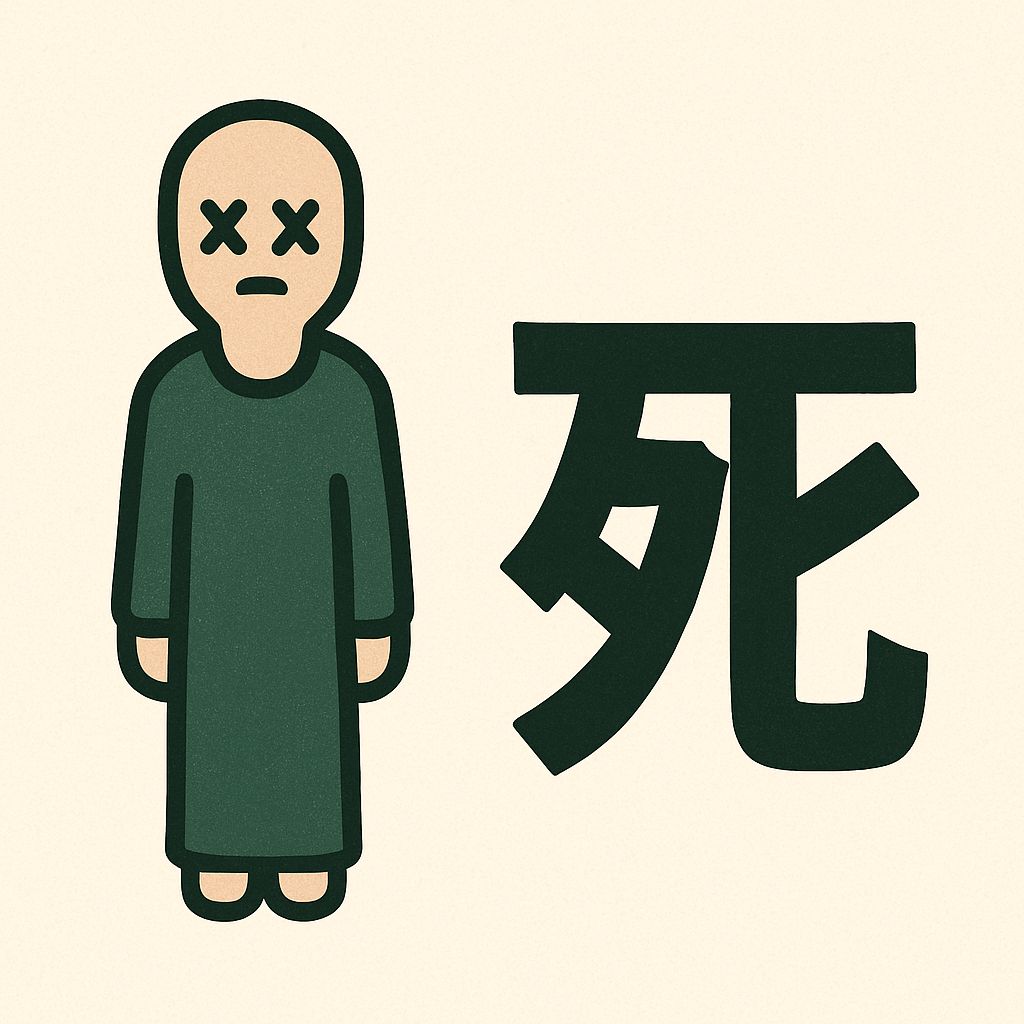

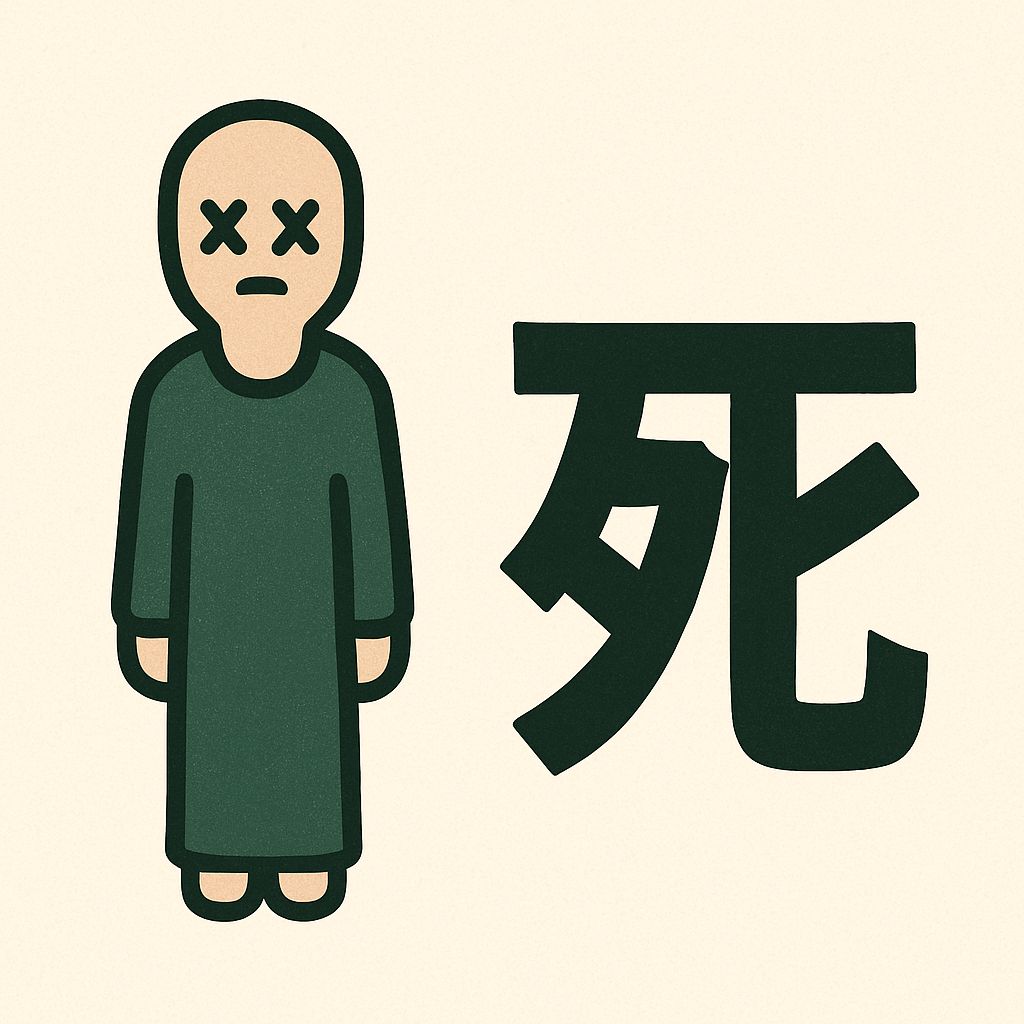

💀 死(し / shi)– death

The kanji 死 means death, both literally and figuratively. It appears in formal, medical, and emotional expressions, and carries strong cultural significance in Japanese.

Reading:

し (shi) – on’yomi (Sino-Japanese reading), used in all modern vocabulary

※ There is no commonly used kun’yomi.

Kanji Origin:

死 (shi) is a compound ideograph(会意文字). It combines the radical 歹 (associated with death or decay) and 匕 (a simplified figure of a person). Together, the character represents a lifeless or deteriorating body, reflecting the concept of death since ancient times.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 死亡(しぼう / shibō) – death (formal term)

- 必死(ひっし / hisshi) – desperate, putting one’s life on the line

- 死体(したい / shitai) – dead body, corpse

- 生死(せいし / seishi) – life and death

- 安楽死(あんらくし / anrakushi) – euthanasia

Common Collocations:

✅ 死にかけた (shini kaketa) – nearly died

事故のとき、本当に死にかけた。

EN: I nearly died in the accident.

✅ 死にそう (shinisō) – feel like dying / extremely tired or in pain

暑すぎて死にそうです。

EN: It’s so hot, I feel like I’m going to die.

✅ 死を迎える (shi wo mukaeru) – to face death

祖父は静かに死を迎えました。

EN: My grandfather passed away peacefully.

✅ 死を考える (shi wo kangaeru) – to think about death

死を考えることは、生き方を考えることでもある。

EN: Thinking about death also means thinking about how to live.

✍️ Notes:

- 死 is often replaced with softer expressions like 亡くなる or 他界する in everyday conversation.

- The reading shi is culturally sensitive and is avoided in some contexts, especially because it shares the same sound as the number 4 (四), which is considered unlucky.

- This kanji appears in many essential terms related to medicine, ethics, and philosophy, making it important for both language and cultural understanding.

🦟 蚊(か / ka) – mosquito

The kanji 蚊 means mosquito, the small insect infamous for sucking blood and spreading diseases. In Japanese life, it’s associated with summer, irritation, and public health concerns.

Reading:

か (ka) – kun’yomi (native Japanese reading), used in everyday speech.

Kanji Origin:

蚊(ka)is a semantic-phonetic compound (形声文字).

- The left part 虫 (mushi) is the semantic component, meaning “insect.”

- The right part 文 (bun) provides the phonetic clue.

Together, they represent an insect (虫) pronounced similarly to 文 – in this case, the mosquito.

Vocabulary Examples:

蚊に刺される(かにさされる / ka ni sasareru)=to get bitten by a mosquito

蚊取り線香(かとりせんこう / katorisenkō)=mosquito coil

蚊帳(かや / kaya)=mosquito net

蚊の音(かのおと / ka no oto)=mosquito buzzing sound

💬 Common Collocations:

✅ 蚊が多い (Ka ga ooi) – there are many mosquitoes

夏になると、この辺は蚊が多くなります。

EN: In summer, there are lots of mosquitoes around here.

✅ 蚊に刺される (Ka ni sasareru) – to be bitten by a mosquito

昨夜、蚊に刺されてかゆくて眠れなかった。

EN: I was bitten by mosquitoes last night and couldn’t sleep because of the itching.

✅ 蚊を退治する (Ka o taiji suru) – to get rid of mosquitoes

スプレーで蚊を退治した。

EN: I killed the mosquitoes with a spray.

✅ 蚊の鳴くような声 (Ka no naku yō na koe) – a very faint/quiet voice

彼は蚊の鳴くような声で「ありがとう」と言った。

EN: He said “thank you” in a voice as faint as a mosquito’s buzz.

✍️ 字(じ / ji)– character, letter

The kanji 字 means character, such as a letter in writing. It’s used for written language, especially Chinese characters (kanji) and Japanese syllabary (kana).

Reading:

じ (ji) – on’yomi (Chinese reading), used in compound words and formal contexts.

Kanji Origin:

字(ji)is a compound ideograph (会意文字).

- The top part 宀 (roof) suggests a house or shelter.

- The bottom part 子 (child) represents a child.

- Together, it originally symbolized a child under a roof, implying education or writing at home, hence the meaning “character.”

Vocabulary Examples:

- 漢字(かんじ / kanji)=Chinese character

- 文字(もじ / moji)=written character / letter

- 名字(みょうじ / myōji)=surname / family name

- ローマ字(ローマじ / rōmaji)=Roman alphabet

💬 Common Collocations:

✅ 字がきれい (Ji ga kirei) – to have neat handwriting

彼女は字がとてもきれいです。

EN: She has very neat handwriting.

✅ 字がきたない (Ji ga kitanai) – to have messy handwriting

医者の字はきたないことで有名です。

EN: Doctors are famous for their messy handwriting.

✅ 字を書く (Ji o kaku) – to write a character

子どもが初めて自分の名前の字を書けるようになった。

EN: My child was able to write the characters of their name for the first time.

✅ 字が読めない (Ji ga yomenai) – can’t read a character

難しい漢字で、その字が読めませんでした。

EN: It was a difficult kanji, so I couldn’t read it.

💢 痔(じ / ji)– hemorrhoids

The kanji 痔 refers to hemorrhoids, a common medical condition involving swollen veins around the anus. Though often seen as a taboo topic, it’s a word many Japanese people recognize, especially in medical or comedic contexts.

Reading:

じ (ji) – on’yomi (Chinese reading), used in medical and formal terms.

Kanji Origin:

痔(ji)is a semantic-phonetic compound (形声文字).

- The left part 疒 is the semantic component, meaning “illness” or “disease.”

- The right part 寺 (ji) gives the phonetic clue.

Together, they imply a disease (疒) pronounced like 寺 – in this case, referring to hemorrhoids.

Vocabulary Examples:

- 痔になる(じになる / ji ni naru)=to get hemorrhoids

- 痔の薬(じのくすり / ji no kusuri)=hemorrhoid medicine

- 痔の手術(じのしゅじゅつ / ji no shujutsu)=surgery for hemorrhoids

💬 Common Collocations:

✅ 痔に悩む (Ji ni nayamu) – suffer from hemorrhoids

長時間座っていると痔に悩まされる人も多い。

EN: Many people suffer from hemorrhoids when sitting for long periods.

✅ 痔の治療を受ける (Ji no chiryō o ukeru) – receive treatment for hemorrhoids

病院で痔の治療を受けました。

EN: I received treatment for hemorrhoids at the hospital.